Circularity and the road to the future

According to the “Circular Economy Roadmap for Germany 2021” report, the transport sector accounts for 24% of all CO2 emissions. This has of course prompted the fast-pace development of the electric mobility industry, which has been booming over the last few years. But is e-mobility alone enough to lead us into a more sustainable future? Certainly not. As the demand for electric vehicles keeps on growing rapidly and governments keep pushing the industry towards a greener mobility industry (the report also mentions Germany’s goal to have seven to ten million electric vehicles on the road by 2030), so should the industry’s practices.

Though there has of course been immense progress on that front, whether in terms of emissions, supply and sustainable practices, we’re not quite there yet. For instance, electric cars only reach a better carbon footprint than regular vehicles after 50,000 to 80,000 km. So the question is, what can be done? At this point, it is clear that the old “take, make, waste” mindset simply doesn’t cut it anymore, and with such high demand for electric and hybrid vehicles, so too comes a high demand for lithium-ion (traction) batteries. As this is expected to continue to increase exponentially in the next decade, so will the need for its components: cobalt, lithium and nickel – which, like any of our planet’s resources, are not infinite.

What is circularity?

This is where the concept of circularity comes in. Most of us are now familiar with the concept of a circular economy, wherein production and consumption are based upon the high value of materials and human activities which are then used in a cyclical fashion, in order to create a model that is transparent, resilient and regenerative both to human beings and our environment.

In mobility, circularity is a bit less of a head-scratcher, and actually much more straightforward: it involves the manufacturing of products with long service lives, and the implementation of practices such as reuse, repair and remanufacturing once said products reach the end of their service life in order to minimise resource usage and environmental impact.

Within the context of e-mobility for instance, this would mean that all materials and products used in production, from the raw materials to refinement, active materials, cell production, and module & system production would have the potential to be reused, repaired or refurbished and recycled at multiple stages of production, rather than simply disposed of after a one-time only recycle.

Why it matters

While the rising demand for electric vehicles holds great potential for new economic value creation and increased prosperity, the socio-economic impacts that can arise from this, such as environmental pollution, occupational health and safety challenges and human rights violations will do much greater harm than good. To put it bluntly, we are destroying our planet without even employing the most efficient and beneficial means of production for ourselves. With the use of the circular model, not only will environmental impact decrease drastically – traction batteries are estimated to emit 40 percent less CO2 over their service life – but resources would be decoupled, and therefore accelerate the market ramp-up of electric mobility in the short and medium term.

According to the Circular Economy Initiative Deutschland report, the circular economy approach “can provide up to about ten percent of the demand for key battery materials in 2030 (up to 40% by 2050) and reduce net costs by up to about 20% over the life cycle of the batteries. The Circular Economy will further contribute to a more resilient economy and minimise dependency on material imports, not only by tapping secondary material sources within the economy but also by supporting economic models that can be exported. This makes a Circular Economy for traction batteries highly desirable for society as a whole as well as for individual companies.”

The road to now

Though the circular economy isn’t a new concept, it has certainly been an uphill battle in many ways, and many industries still have to catch up to the reality of their current wasteful models. Still, there have of course been some promising initiatives in the last few years. In 2020, over 100 global organisations and 200 executives joined together in the Circular Cars Initiative, which launched at Davos 2020.

This partnership between stakeholders from the automobility ecosystem has pledged to eliminate or minimise total lifecycle emissions with a special emphasis on manufacturing emissions. The initiative’s overarching goal is to achieve an automobility system that is convenient, affordable and firmly grounded within a 1.5°C climate scenario by 2030.

Renault’s ReFactory

Another impressive initiative has been the ReFactory founded by the Renault Group in 2020 and the first European circular economy site dedicated to mobility. By 2030, it will employ more than 3.000 people in dedicated professions.The implementation of this industrial and commercial ecosystem is currently taking place and set to reach its goal of replacing the production of new vehicles by 2024. will take place gradually between 2021 and 2024, replacing the production of new vehicles.

To support this approach, the ReFactory will also include an incubator open to start-ups, academic partners, large groups, local authorities and intrapreneurship, as well as a training centre backed by a university to promote know-how and accelerate research in the circular economy framework. Renault is also already employing many of the founding principles of circularity in the production of their most popular vehicle, the Renault ZOE , made with 22.5kg of recycled synthetic materials.

Mercedes-Benz’ circular approach

The Mercedes Benz Group AG is another company with a strong commitment to circularity. Already in 1996, ahead of many of its peers, the brand set up the Mercedes Benz Used Parts Center , created to disassemble over 5.000 vehicles per year to reuse their parts. Then, used Mercedes-Benz genuine parts are reconditioned within the framework of the company’s remanufacturing approach and used in a second automotive life cycle.

As for reutilisation, they’re on track too: the parts that are no longer suitable for remanufacturing are repurposed whenever that is possible, for example with batteries that are no longer suitable for reuse in a vehicle and thus reprocessed for use in a stationary energy storage unit. Finally, if parts are no longer suitable for reuse, they are recycled with the aim of retrieving as much as possible of the recyclable materials they contain. These circular practices, along with their implementation of a value-added cycle rather than a value chain, makes the group a leader in the circular mobility sector.

Volvo’s sustainability goal

Of course, there are many initiatives currently being put in motion that show some real promise. For instance, Volvo – which also has been doing quite well on the reuse, reutilise, remanufacture and recycle front with 4.000 tonnes of CO2 saved in 2021 by remanufacturing over 37.000 parts – has set itself a set of circular economy ambitions. In short, the brand aims to increase the share of sustainable recycled and bio-based materials in their cars by 2025, including 25% of recycled or bio-based plastics, 40% recycled aluminium, and 25% recycled steel.

Their overarching goal however, is to be a fully circular business by 2040: “We’re changing our company, value chain and industrial system. We commit to being transparent throughout this transformation. We’ll act responsibly and we’ll continue talking with stakeholders inside and outside of our industry.” They have even posted position papers about circular economy, carbon offsetting and climate action in an effort to be more transparent, a step that should inspire many more within the industry. Last year, we were invited to take part at the Volvo Studio Ulm where we asked various questions from all of you about Volvo’s sustainability practices which might shed some more light on their positions. For instance, Olaf Meidt, Head of Press and PR Volvo Car Germany told us: “Volvo did a lifecycle assessment to find out how much CO2 in total is needed to develop and produce a car. The XC40 as a combustion engine is relatively good when the car is being built. The XC40 Recharge, so the electric model is 40% worse in terms of CO2 footprint than the internal combustion engine. However this is getting better over the lifecycle. When the XC40 Recharge is being charged with green electricity, after 47.000 kilometres the break-even is reached. So after that you are travelling more sustainably than with the combustion car.”

Toyota’s dismantling strategies

Toyota – which has also been a big recycler since the 1970s – is now also putting a stronger focus on their hybrid vehicles recycling, as well as depollution and dismantling, most notably by manufacturing vehicles with dismantling in mind. For example, they create V-shaped grooves at the points in the bodywork where the instrument panel is attached, making it easier to remove, or by marking certain parts with an Easy to Dismantle symbol to show clearly where they can be most easily taken apart and sorted into different material streams for recycling.

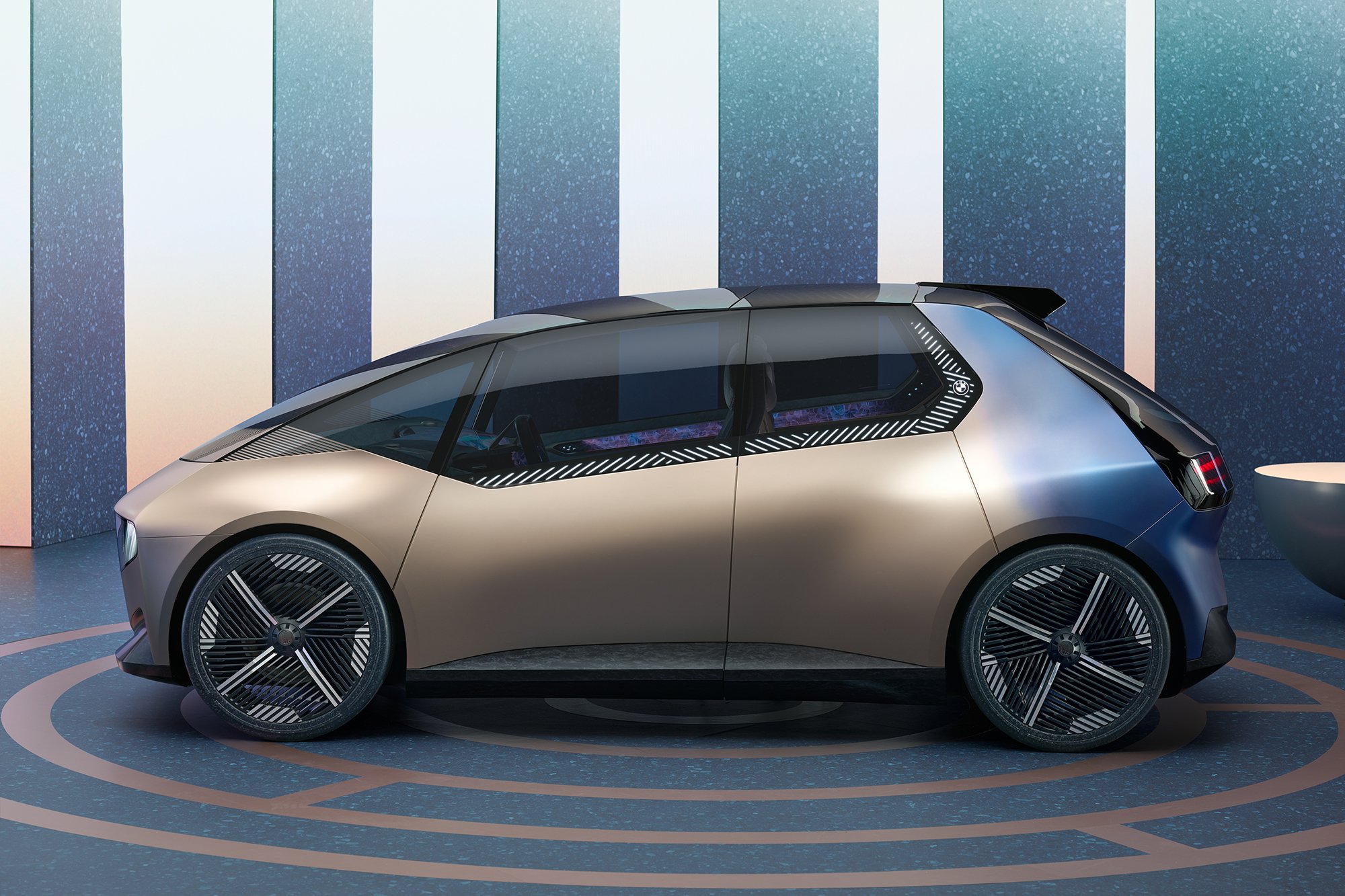

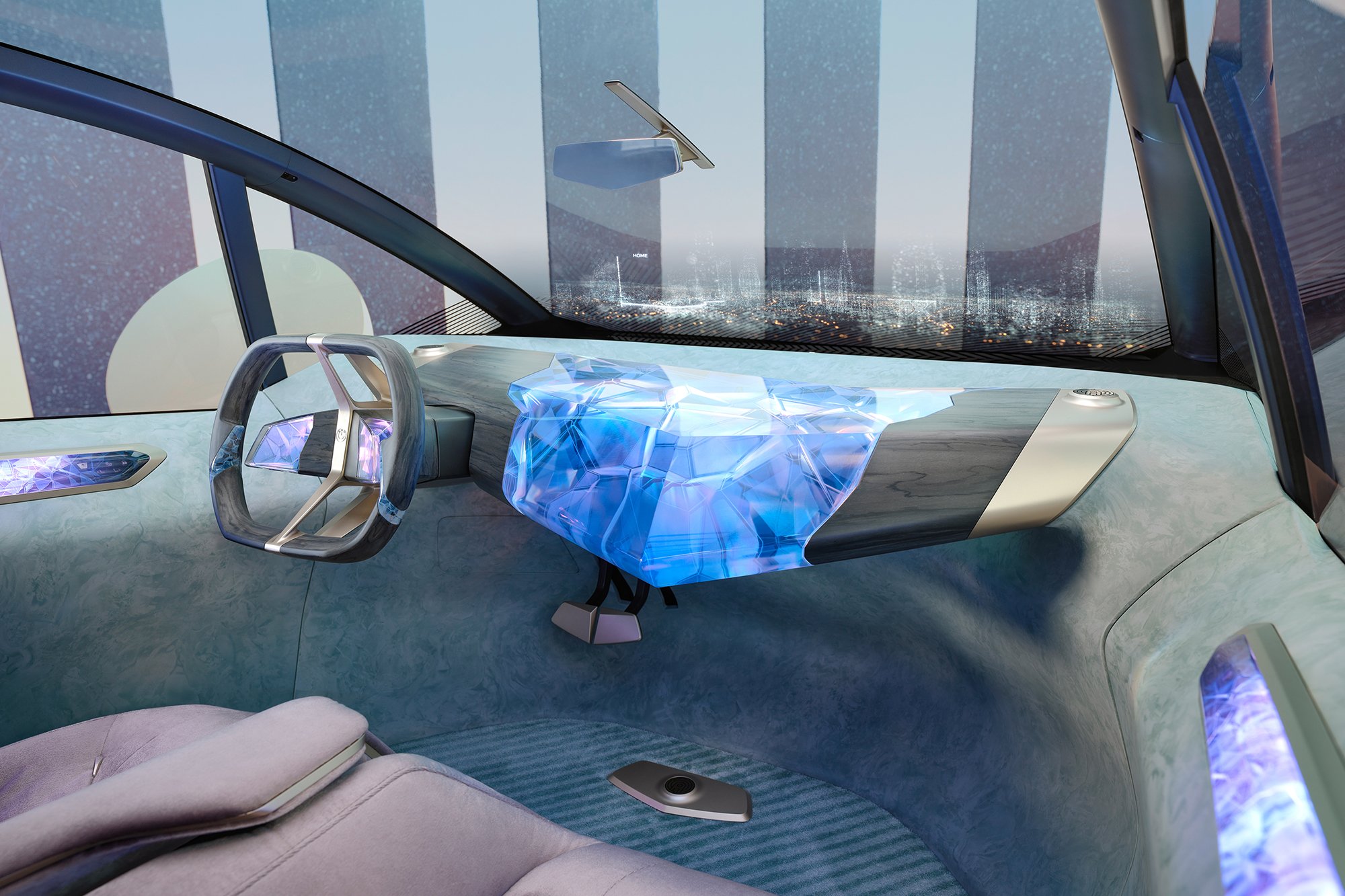

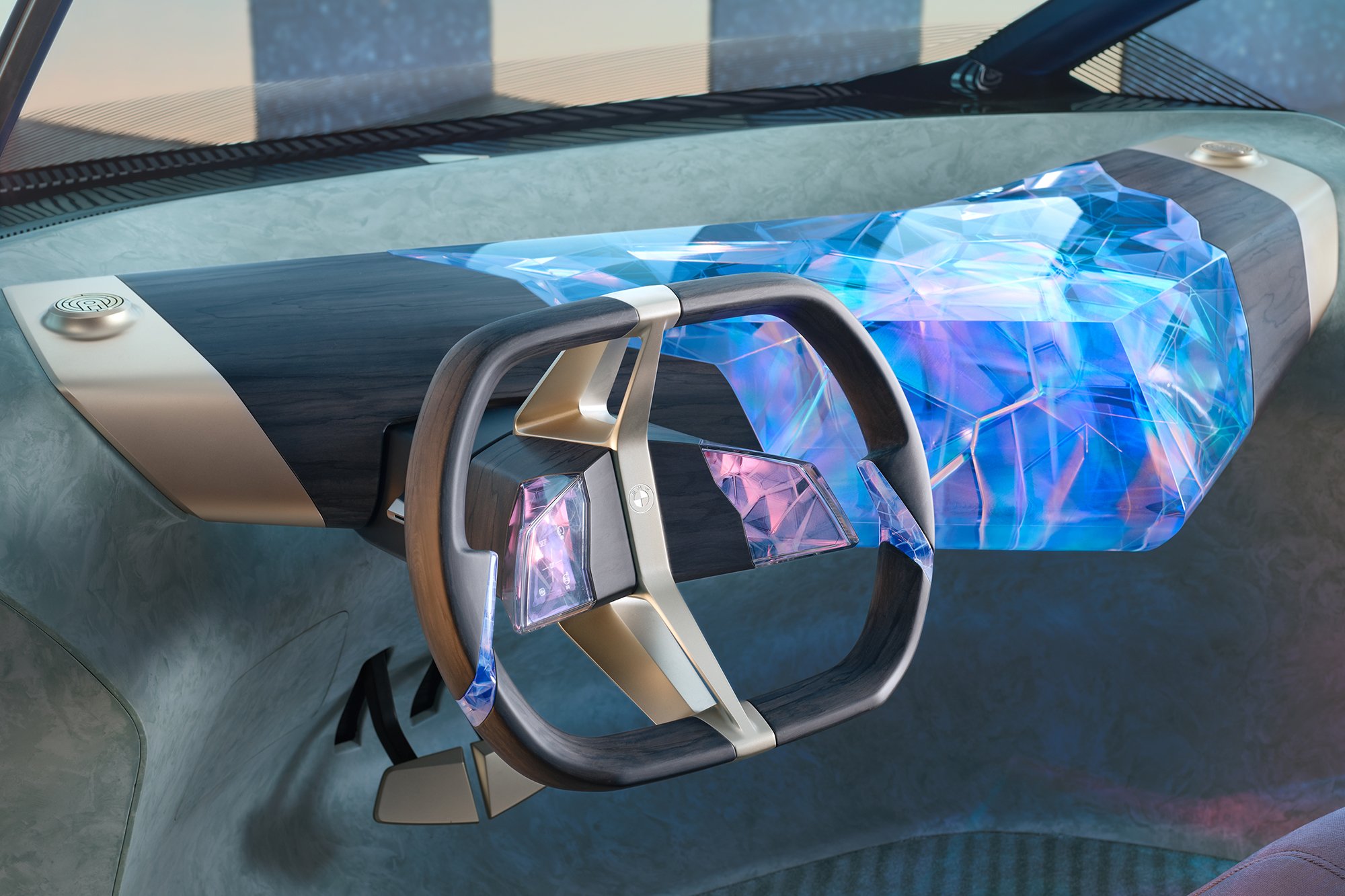

BMW i Vision Circular

Last but certainly not least, the BMW Group has also been cooking up some interesting circular projects, including the BMW iVision Circular, a futuristic and compact concept car set to release by 2040, focused on luxury and sustainability – because no, they don’t have to be mutually exclusive.

The four-seater is fully electrically powered and offers a generous amount of interior space within its four-metre-long footprint. The overriding aim in the design of the BMW iVision Circular was to create a visionary vehicle that is optimised for closed materials cycles and has the goal of achieving 100% use of recycled materials or 100% recyclability. With their own twist on the four Rs, “re:think, re:duce, re:duce and re:cycle,” the company is set to be a leader in circular mobility.

“Sustainability isn’t just something we do at BMW: we are making BMW sustainable.” – Oliver Zipse, Chairman of the Board of Management at BMW AG

We still have a long way to go in order to reach a fully circular economy approach to the mobility sector, but it’s reassuring to see that we’re at least well on the way there – and that it doesn’t have to mean giving up on luxurious driving pleasure or fantastic design.

Picture 1: ellectric

Picture 2+3: Renault Group

Picture 4+5: Volvo Germany for ellectric

Picture 6-9: BMW Group